Launching 1st March 2023. Also check out: https://www.thailandmedical.news/

Innovation is something of a buzz-word in modern medicine and rightly so. In order to deliver the best care and treatment to patients it is crucial that we are open to new ideas and encourage scientific advancement.

Finding new ways to successfully convert novel ideas into day-to-day practice is crucial to improve healthcare. However, all too often our focus on innovation is on new technologies, new scientific methods, or new drugs – it becomes a quest for the ‘next big thing’.

These are unquestionably important for treatments to be developed and reach patients; however, they are not the only form of innovation, and arguably not the form of innovation most needed in modern, cash-strapped healthcare systems.

Credit: Costello Medical Consultancy and Findacure

Innovation is also equally about innovative ideas – finding new ways to deliver a service or improved ways to use current resources. Drug repurposing is an excellent example of this form of innovation: using a scientific approach to identify new uses for existing drugs.

This type of research is clearly less ‘sexy’ than the development of novel treatments or advanced therapies like gene editing, as it does not produce an exciting new molecule or genetic construct. Subsequently people tend to believe that a repurposed therapy can never be truly novel or transformative, it just offers an incremental improvement.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The repurposing of one of the first monoclonal antibodies is a great example. It has been repurposed from cancer into multiple sclerosis, acting to effectively boost the immune system to protect against the disease’s degenerative effects. This is a novel mechanism to treat the condition derived from repurposing research: clearly a great form of innovation.

Credit: Costello Medical Consultancy and Findacure

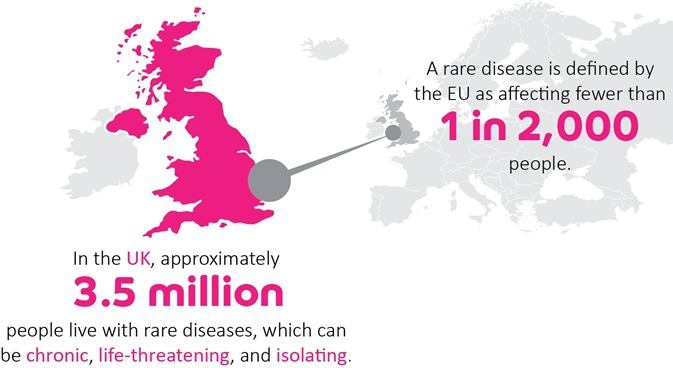

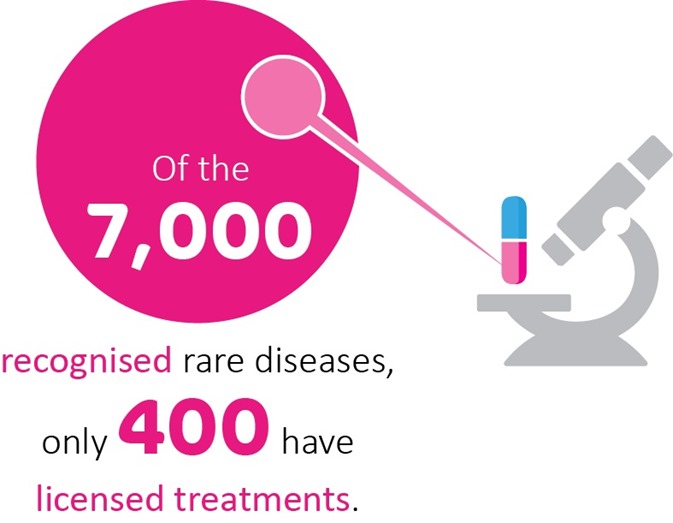

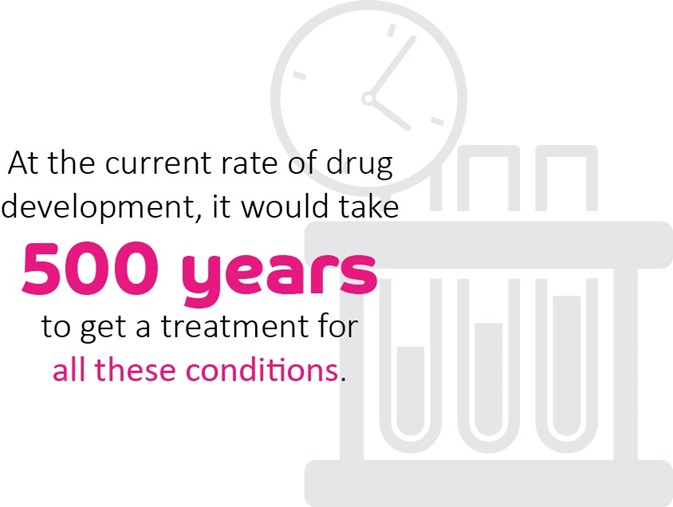

Drug repurposing has real promise for rare genetic conditions. There are over 7,000 different rare diseases and, with rapid advances in genomics, the number is constantly expanding. Unfortunately, only around 400 have licensed treatments, which leaves millions of people worldwide with little hope of disease-altering clinical support.

However, our ability to understand the underlying mechanisms of such unsolved diseases is also expanding with the rise of genomics. It is in these conditions that repurposing has its greatest potential.

Firstly, potential to deliver a meaningful and novel disease modifying treatment to a previously ‘unsolved’ disease, simply by matching drugs to impaired biochemical pathways. Secondly, repurposing offers a real chance to deliver this treatment relatively rapidly, and potentially inexpensively, to patients.

Credit: Costello Medical Consultancy and Findacure

Drug repurposing works in two distinct phases: identification of candidate drugs and testing of their effect.

The identification of repurposing opportunities is a burgeoning field of innovation, which can span simple clinical serendipity, advanced text mining approaches, and analysis of gene expression patterns.

Traditionally, serendipity has been a major driver in drug repurposing. The treatment of leprosy is a classic example. With no viable treatment clinicians were simply left to manage the symptoms of this devastating condition. Patients often suffered from severe discomfort and pain, preventing sleep.

One of Israeli physician Jacob Sheskin’s patients suffered so severely from this, that he felt compelled to prescribe a drug originally marketed as a sedative, which was prescribed to pregnant mothers with disastrous consequences for the development of their children. This treatment not only helped the patient sleep, but began to have a rapid impact on the patient’s other symptoms. This drug is now used as an effective treatment for leprosy, its side effects well understood and managed.

This type of serendipitous repurposing makes for an excellent story, but a poor route to deliver a wide range of new treatments to patients. More often clinical-led innovation is based on an individual’s knowledge of disease progress or drug targets and side-effects. This type of expert driven repurposing has been the norm for years.

Recently however, things have begun to change. Firstly, drug screens have become increasingly prevalent, as a simple route to identify compounds with potential therapeutic effectives in a target disease.

In repurposing studies, prior knowledge about disease and drug mechanisms can also help to construct ‘intelligent’ screens, which specifically target a small set of drugs thought to act on the relevant pathway.

Beyond screening technologies, the wealth of data available in the digital age has spawned many new data analytic techniques that are helping to drive a more systematic approach to repurposing. Text mining approaches are allowing bioinformaticians to search the published scientific literature for connections between drugs and diseases.

In its simplest form, text mining identifies co-occurrences of drug and disease terms in the same sentence across hundreds of thousands of scientific articles. This allows a much more comprehensive review of published papers than can be managed by researchers alone.

Furthermore, new advances in natural language processing and machine learning allow computer algorithms to go beyond the sentence structure and infer connections between drugs and conditions that are not explicitly mentioned in the text. While such inferences still require extensive evaluation by human experts, they could provide a gateway to some truly novel repurposing opportunities.

Another exciting innovation is the field of transcriptomics – essentially the study of all of the genes that are active in the body’s cells. The genes that are active in a cell and the level to which they are used determines how a cell functions.

In genetic diseases, the expression of certain genes is likely to be very different to those of unaffected individuals. This produces a specific ‘transcriptomic signal’ for certain diseases in certain cells. Drugs can also alter the expression of genes in the body, as such they too can have a ‘transcriptomic signature’.

A new approach to repurposing is to attempt to identify the transcriptomic signals of specific drugs that are the opposite of the signals for a disease. In theory, this should allow the drug to cancel out the disease signal, normalizing the gene expression in affected cells, and eliminating the disease symptoms.

This type of approach is very new, but has great promise. The team at the Cambridge biotech Healx have recently used these methods to identify a potential repurposing candidate for the rare disease CDKL5.

After a repurposing opportunity is identified, the second major component of a repurposing study is the proof of concept. This is the completion of rigorous preclinical and clinical trials to test the effect of the candidate drug in the patient population. While this follows the same basic rules used in any drug development process, repurposing does offer a few key advantages.

Firstly, repurposing uses compounds for which a large amount of detailed information is already known. Its absorption by the human body, its effect in its licensed condition, its side effects in diverse human population, its tolerability, and even its effect in a range of secondary conditions are all likely to be well known and documented.

This prior knowledge is the biggest advantage in repurposing. It not only helps to speed the identification of viable repurposing opportunities for a condition, it can also act to lower the need for early stage clinical trials which test drug absorption and tolerability in humans.

Removing such steps in the clinical pathway helps to reduce the time drugs take to reach clinic and spend on clinical development. This has the potential to lower development costs, which one would hope could lower the price of the drug on the market.

Credit: Findacure

A final key consideration with repurposing is success rate. Due to higher levels of knowledge about the candidate drug’s behavior in humans from the very start of the project, repurposing projects are much more likely to advance to clinic than novel drug discovery.

While the latter is estimated to have a success rate often in the single figure percentages, repurposing projects are estimated to be delivered successfully in about 30% of cases.

Indeed, the US based charity Cures Within Reach conducted a survey of the 200 research projects they had funded 1998-2009. They found that none of the 190 de novo projects had touched patient lives, but 4 of the 10 repurposing projects had delivered patient benefit, and subsequently switched all of their attention and funding to repurposing.

Due to the new innovations in identifying drug repurposing opportunities, the relatively low financial bar to enter the space, and the increased likelihood of repurposing success, it is a field of drug development that is open to groups beyond the pharmaceutical industry.

Biotechs, academics, and clinicians are all able to play a significant role, sourcing new ideas or developing them for the market.

More excitingly still, patient groups – charities, often rare disease focused, set up to promote the interests of a specific group of patients – are beginning to drive repurposing research forward. Such groups can act as funders for projects to identify repurposing opportunities for their condition, provide samples and expertise necessary for such projects, or help to plan and recruit for clinical trials.

While repurposing research is becoming more prevalent, it still struggles to receive the recognition or funding it deserves. It is for this reason that Findacure, Healx, and Cures Within Reach have come together to launch the Rare Repurposing Open Call.

This three-month project is a chance for the rare disease community to come together and share their repurposing ideas that are struggling to receive the funding and support they need to be fully tested and delivered to the patients that need them.

We all believe that repurposing offers real potential to rare disease patients, many of whom lack even the hope of treatment. By launching this call we hope to highlight the potential power of repurposing for this underserved group, and help to attract the funding and support they need to deliver real change.

Dr. Rick Thompson joined the UK rare disease charityFindacure in 2015, after completing his PhD in Evolutionary Biology at the University of Cambridge. As Head of Research, he is responsible for all scientific projects, with the aim of developing a socially financed drug repurposing program – Findacure’s rare disease drug repurposing social impact bond (RDDR SIB).

Rick has designed and completed a proof of concept study to demonstrate the feasibility of the RDDR SIB to the NHS, investors, industry, and patient groups. He also works to encourage industry engagement with rare disease patient groups, promoting an open and collaborative approach to rare disease research.

Disclaimer: This article has not been subjected to peer review and is presented as the personal views of a qualified expert in the subject in accordance with the general terms and condition of use of the News-Medical.Net website.